Scoping an FDIC Model for Cislunar and Interplanetary Economic Activities

Part Two of Our Series on Space Economic Assurance

This is part two of a two part series on space economic assurance. Please read part one here.

Big Risk, Big Insurance

The $1.2 billion invested in three companies building technology for cislunar missions was not spent to build and test things on earth. It was spent to put that equipment in space. Not low earth orbit. Cislunar. At least.

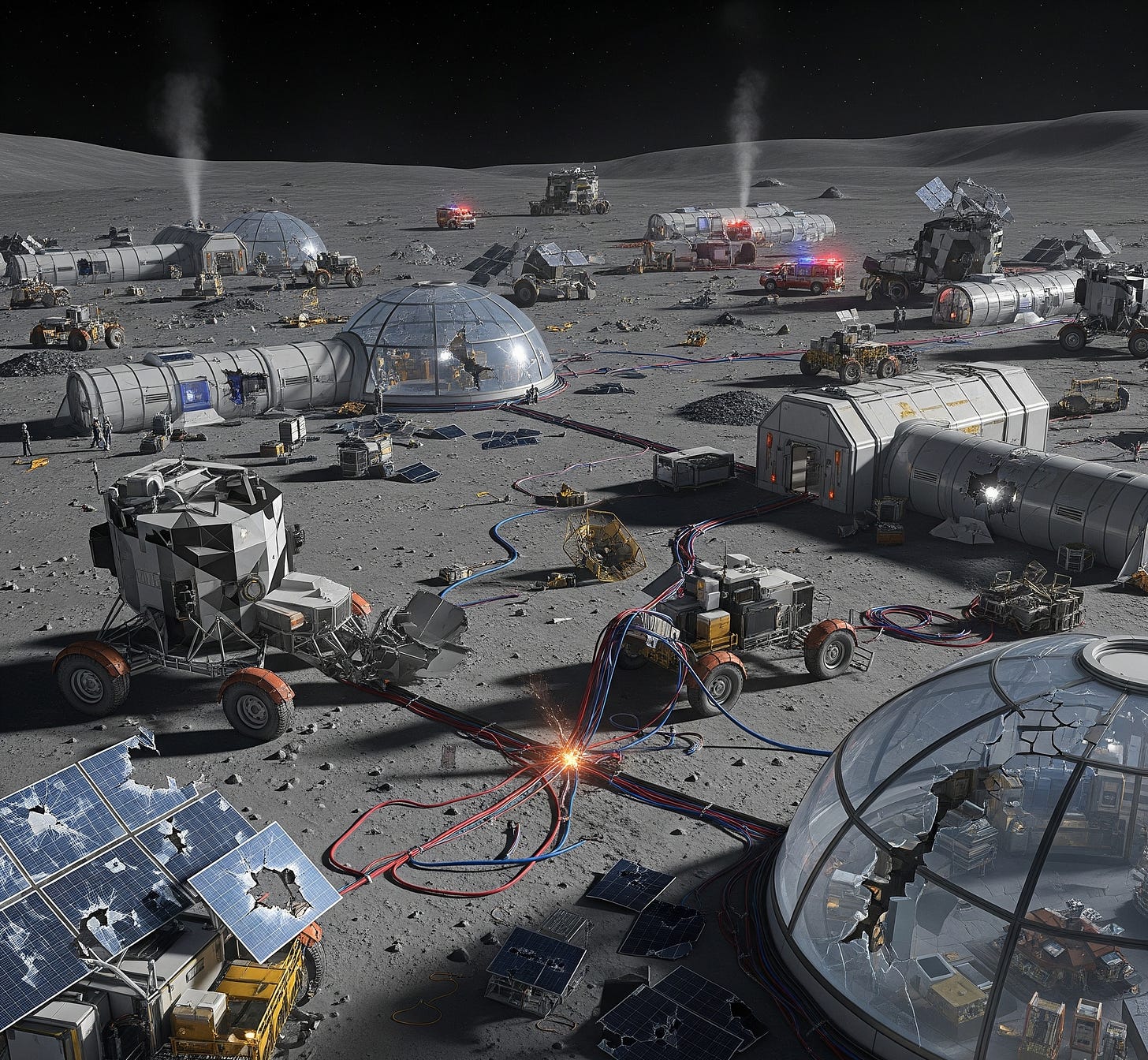

The sheer volume of equipment that would need to be carried to the Moon at minimum and potentially into interplanetary space to facilitate the extraction of economically viable resources is hard to imagine currently. Several pieces of the cislunar and interplanetary puzzle would need to be solved such as common use infrastructure and a significant reduction of launch cost per kilogram. Assuming those things are true, that only solves part of the problem. Getting the equipment there is a huge step but operating it to a capacity that will produce economic returns is another matter.

Investors in such an endeavor will have put forward significant capital over and beyond the $1.26 billion spent on just the three companies listed above. They will be unlikely to see returns for a decade or decades. Setbacks will be inevitable as companies test new technologies (some of which will fail in the space environment) and discover challenges that were not anticipated. Under these conditions, investors will want to see progress toward returns applying pressure to companies to push the boundaries.

The potential for such massive revenue will also motivate malicious actors that could implant a Stuxnet-style exploit in what will be an entirely new category of space operational technology (SOT). Such an exploit could enter the supply chain years before on the ground and be held in abeyance until the SOT is live. Having humans on cislunar or interplanetary bodies consistently will require some amount of space critical infrastructure such communications…which will be vulnerable to exploitation. There’s also the potential for misinformation that could impact and apply pressure to companies and investors.

In short, there’s a lot that can go wrong.

Back on the ground, the companies that will execute this kind of operation will need to be massive, which means massive funding. It also means huge numbers of workers, likely government funding, and multinational sources. Combined, the value of a company, or a conglomerate of companies, would be on a scale that we’ve likely not seen on earth. A catastrophic failure of an economically viable and profitable space mining operation will have the potential to impact national or international economies. If just three companies have drawn $1.2 billion of investment BEFORE any profit-seeking mission is launched, the extrapolation of that investment is at least an order of magnitude higher. That kind of commercial venture comes with enormous macroeconomic risk that could impact huge swaths of the global economy if not managed correctly.

The has experienced the failures of privately owned entities that threatened its economy at the national level multiple times from the Bank of the United States to the failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008. In 1930, the failure of Bank of the United States and 9,000 others over a four-year period led the formation of the FDIC. The FDIC and its model of overseeing money input by the specific industry it is charged with protecting led in large measure to the restoration of confidence in a broken financial system. Following that success, it played a direct part in averting the loss of billions of dollars in potential depositor loss and helped to prevent the failures of countless other banks through its audit and supervision functions. Cislunar and interplanetary economic ventures need the same assurance.

Modeling Assurance

Not so long ago, space activities were the exclusive domain of the handful of rich countries that could afford to launch them. That’s changed largely due to the drop in launch cost per kilogram and advances in other technologies. The drop in costs opened the domain to economic players and other smaller countries previously not able to participate due to restrictive costs. That this is now different is a good thing and it opens the door for new economic value creation and potentially as a source of the raw materials running in ever shorter supply on earth. The risk and scale of these operations are in no less doubt than the potential economic value. That means that companies need to build this reality into their plans and the technologies they field. It also means they need to be compelled to provide the assurance of their missions.

With what is certain to be some of the highest investments in history to make off-world mining a reality, catastrophic failures could cause real economic damage. This kind of damage will have ripple effects that go beyond the single or multiple companies involved in the specific venture. There will be economic impacts to the consumer industries, defense industrial bases, and beyond. National governments cannot be expected to come to the aid of every failure in cislunar or interplanetary space. They can’t.

The answer is to create a centralized FDIC-like insurance vehicle with government oversight. The companies launching missions into cislunar or interplanetary space that intend to be at least semi-permanent, operate SOT, and have humans onsite should be required to pay into this fund. The fund is used explicitly to cover a portion of response and recovery efforts in the event of a catastrophic failure. Without such an assurance mechanism, commercial companies will assume very little or no financial risk from a failure knowing a government entity is covering the response and recovery efforts.

The establishment of the FDIC restored confidence in the financial system, and a similar model will build confidence in cislunar and interplanetary economic efforts. Investors, consumers, and governments will have a confidence in these operations knowing that the potential economic impacts will be mitigated in the event of a failure.

The motto “failure is not an option” was coined during the worst space disaster involving humans. That disaster was mitigated and the humans made it home safely. They were also dealing with a far less complicated spacecraft that was able to get on a free return trajectory even disabled. What will be involved in a semi-permanent, economically viable cislunar or interplanetary operation will be orders of magnitude more complex and more expensive. There is no parallel we can look on and say that future operations will be similar. This will be without precedent.

It was cold in December 1930, but the uncertainty stung much worse. The people outside of Bank of the United State in the Bronx were in the middle of something they couldn’t yet understand. But it was already underway. The time for mitigating action was months or years before. Not in 1930. What was wrong was already wrong.

The commercial space industry has an opportunity. It can learn from past mistakes in other industries and take corrective action before the big one hits. The evidence to suggest that this kind of assurance model is required is clear. The impact that FDIC had on the financial industry is clearer. Right now, the commercial space industry is comfortable in LEO, but there is more economic value to be had. Realizing that value will require building the foundations that make the investments in the technologies that take us past LEO possible. Part of that is the critical infrastructure that these missions will need. Part of that is the assurance that gives confidence these missions can return real value.

An absence of confidence can feel a lot like a winter day in New York. Just ask those that stood outside Bank of the United States in December 1930.