The Technology Venezuelan Oil Needs is Not Simple or Cheap

A Look at What Oil Investment in Venezuela will Need to Buy

As we neared the bridge tunnel, I called out again:

“Bridge, combat. As of 1022, combat holds the ship 50 yards right of track. Nearest hazard to navigation is shoal water 100 yards off the port bow. Nearest aid to navigation is red buoy 7, 200 yards off the starboard bow. Combat holds distance to turn 1030 to course 255.”

Every two minutes I had to take a measurement from distances to RADAR points called out to me by a friend sitting on a scope to my right. The quartermasters on the bridge were doing the same only with visual bearings and the two were compared to help navigate an 844-foot, 41,000-ton warship through a channel just wide enough to accommodate it.

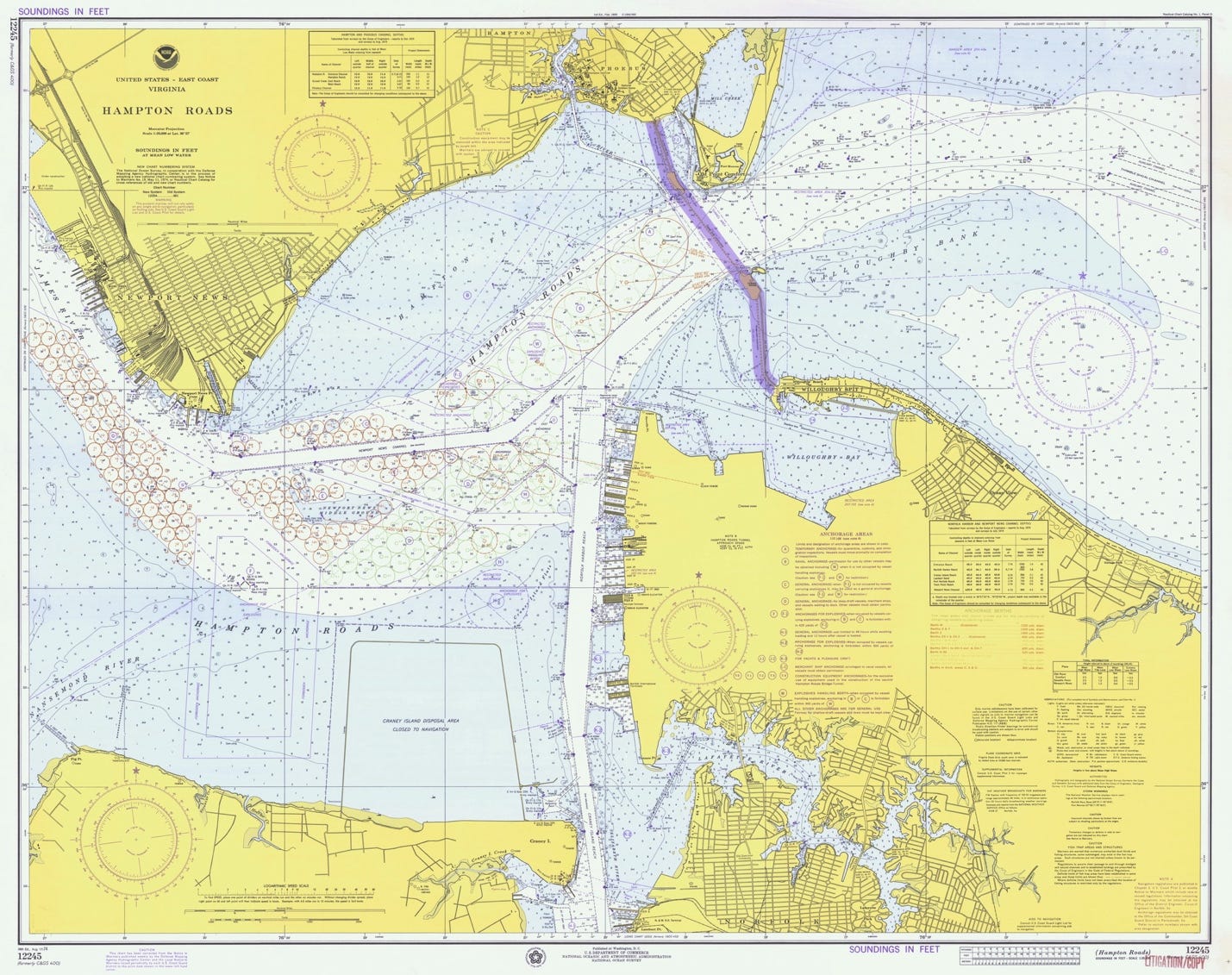

My day job was air defense but in close quarters navigation, I got to work on my side skill. The full trip from the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay to Naval Station Norfolk went on for around three hours. I’d done this route so many times that I could tell you exactly when we would encounter the three sisters or just how long it took from the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel to the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel.

Chart of Hampton Roads Channel to Naval Station Norfolk

It was late December 2006, and I didn’t mind being on watch. It had been a long year full of watches for me and the rest of the 3,000 people onboard as we returned from my third deployment onboard. There’s nothing like homecoming for navy ships after a long deployment. Sailors in their dress uniforms man the rails, massive crowds of loved ones cheer and hold up signs from the pier, and the tugboats spray their fire hoses in the air to welcome you home. I experienced this in 2003 and was happy to let others have the experience that day.

Once we were tied up on the pier, I gathered my things, hugged a few friends, and left the ship to meet my parents. It was the final time I was onboard USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7) after five years of service onboard.

Almost exactly 19 years later, the USS Iwo Jima had another passenger that would step off for the final time, the President of Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro. There are ships in the navy and there are ships that make history. USS Iwo Jima has always found its way into world events and my mother claims she has the gray hairs to prove it. What happens to Maduro and his wife in the coming weeks and months is not certain nor is the future of Venezuela after President Trump’s promise to “run the country” for an indefinite amount of time. What is certain is that Venezuela’s position atop of the largest proven reserves of oil was a major factor.

President Trump has assured the American people that American oil companies are going to go into Venezuela and “pay” to rebuild Venezuela’s oil infrastructure and promises huge oil profits for the US and Venezuela. Whether this is true remains to be seen, but “rebuilding infrastructure” for Venezuelan oil is not that simple because the oil Venezuela sits on is not what you are thinking.

Leaving the geopolitics aside for a moment, we are going to look at the technology required to get Venezuela’s oil running at the scale promised. While MANY other factors are required to make this reality, the technology required places a new perspective on this moment in world affairs.

Sweet and Sour, Light and Heavy

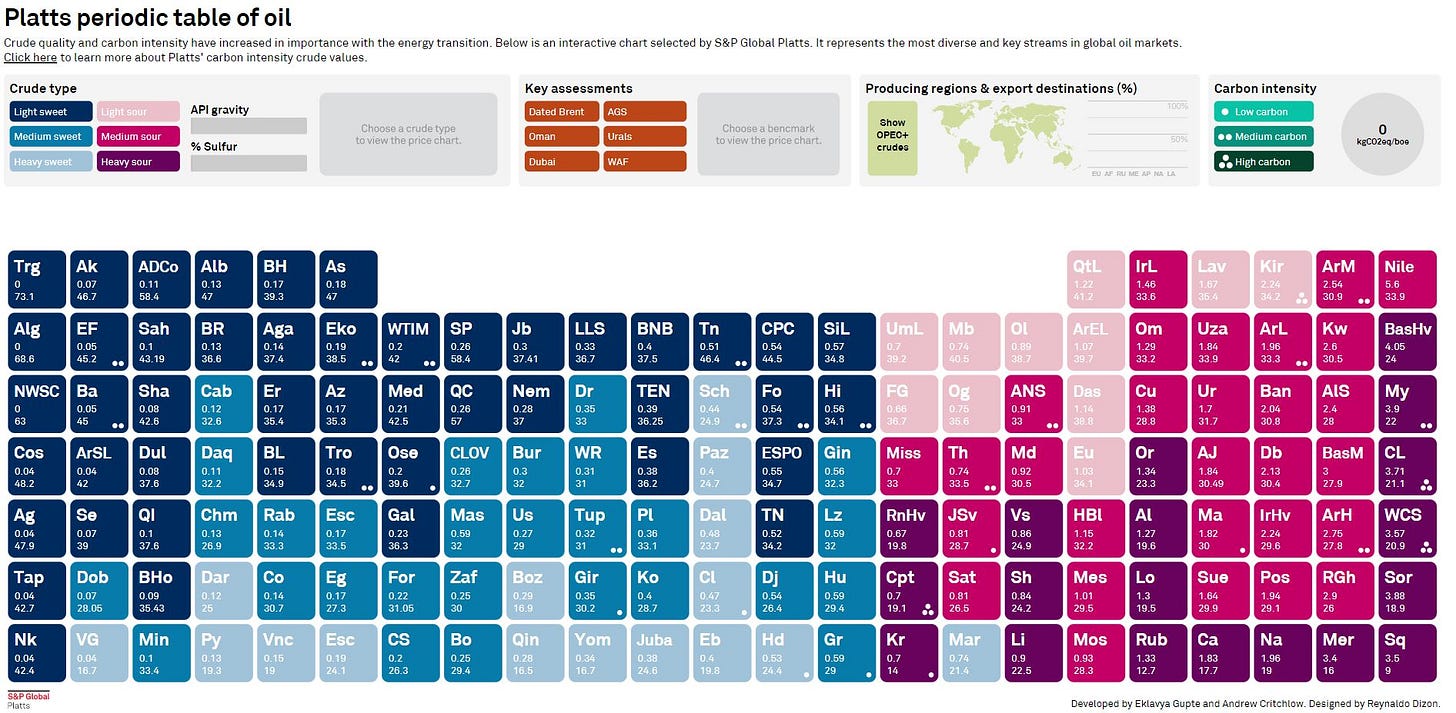

Not all oil that comes out of the ground is the same. It comes down to two factors:

Sulfur Content

Density (API Gravity)

When someone refers to oil as “sweet” they are referring to the sulfur content. Oil that’s high in sulfur will corrode pipes and is worse for the environment when burned. The term “sweet” comes from early oil prospectors that actually tasted the oil out of the ground because the sulfur content gives it a rotten egg taste and low sulfur oil has a slightly sweet taste.

Sweet Crude is less than .5% sulfur

Sour Crude is above .5% sulfur

Density refers to the ability for the oil to flow like a liquid, which matters for how easy it is to get out of the ground. API Gravity is a measure of the density of oil relative to the density of water. Water has an API Gravity of 10 degrees and light crude is anything greater than 30 degrees. This means the oil is less dense than water and can float on top of water in the oil sheens that you’ve seen in puddles in streets or parking lots. Heavy crude is anything less than 20 degrees.

A standard by which oil is judged is West Texas Intermediate (WTI), which is very sweet and very light. It is therefore easier to pump, easier to refine, and has a higher volume of hydrocarbons. It is roughly the consistency of olive oil and is mostly free of impurities that would need to be refined out before production. WTI often results in high quality petroleum products such as jet fuel.

If WTI is sweet and light, Venezuelan oil is heavy and sour. If you think of WTI as something like olive oil, Venezuelan crude is closer to peanut butter that’s been in the fridge. The olive oil flows easily through extraction pipes and requires little refining before it goes to market. Venezuelan oil is more like tar and would need to be heated or have chemicals added to it in order to get it out of the ground. This matters because it directly impacts the costs of extraction and the supporting infrastructure.

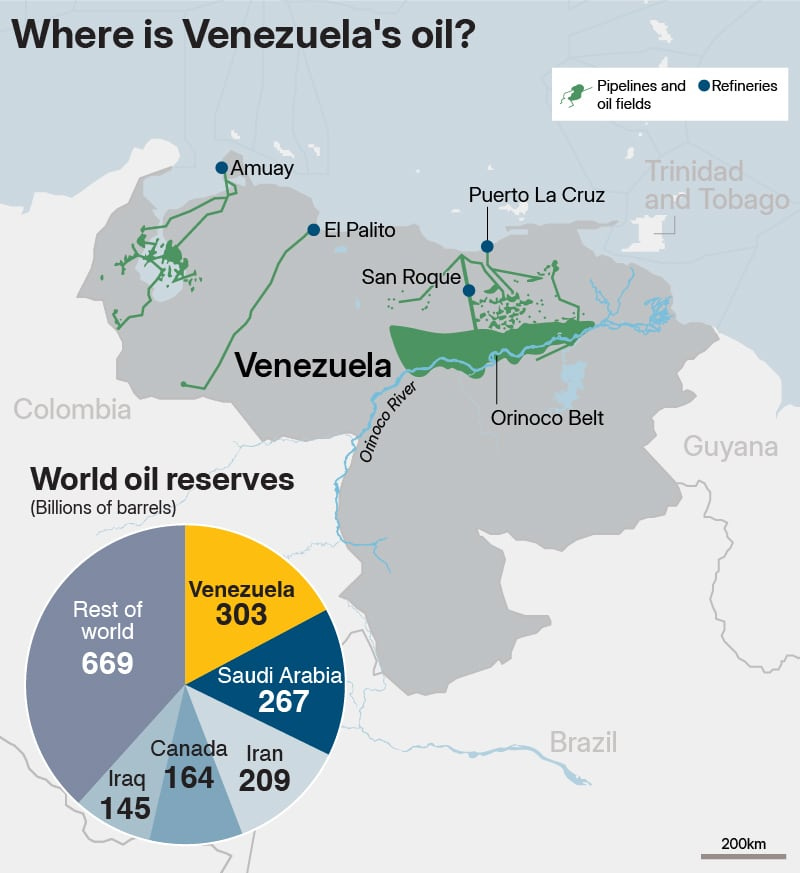

The Tech

Venezuela’s oil comes from the Orinoco Belt, an underground reservoir sitting below a biodiverse area of the country. Its oil is classified as “extra heavy” due to the amount of impurities with an API Gravity of 8-12 degrees. To capitalize on this reserve, significant technologies not required for the extraction and reinfing of WTI are required, called enhanced oil recovery techniques or EOR. The technology required breaks into extraction, refinement, and supporting infrastructure.

Extraction

Because Venezuela’s oil is so heavy, it won’t flow naturally. To get it out of the ground a variety of techniques must be applied like adding “blood thinners” to the oil to make it less like refrigerated peanut butter that sinks in water.

Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD): This involves drilling two horizontal wells, one above the other. High-pressure steam is injected into the top well to heat the surrounding bitumen, reducing its viscosity so it can drain into the bottom well for pumping.

Cyclic Steam Stimulation (CSS): Also known as “huff and puff,” steam is injected into a well for several weeks, allowed to “soak,” and then the same well is used to pump out the thinned oil.

Cold Heavy Oil Production with Sand (CHOPS): This method intentionally produces sand along with the oil to create “wormholes” (high-permeability channels) in the reservoir, though it is less efficient for the deepest extra-heavy deposits.

Diluent Injection: At the wellhead, light hydrocarbons (naphtha or light crude) must be mixed with the heavy oil to make it fluid enough to move through gathering lines.

Refining

You can’t refine Venezuelan crude in standard refineries. Instead, you need multi-billion dollar upgrader facilities that turn the heavy bitumen into lighter synthetic crude.

Delayed Coking: This thermal cracking process breaks down long-chain hydrocarbons into lighter products (gasoline, diesel) and leaves behind petroleum coke (a solid carbon byproduct).

Hydrocracking and Hydrotreating: These units use hydrogen and catalysts at high pressure to remove high concentrations of sulfur and heavy metals (like vanadium and nickel) that characterize Venezuelan oil.

Fractionation: Separating the upgraded oil into various boiling-point components for further refining or export as “Syncrude.”

Supporting Infrastructure

All of the above depends on consistent power, in very remote areas, strong supply chains, deep water port facilities, and specialized pipelines that can handle thick, sulfuric oil as it is extracted. Oh, and political stability.

Stable Power Grid: Upgraders and steam injection plants are massive energy consumers. The Venezuelan grid requires a total overhaul of its hydroelectric and thermal plants to prevent the blackouts that frequently freeze production.

Diluent Supply Chain: Venezuela currently lacks enough light oil to dilute its own heavy production. A massive infrastructure for importing and transporting naphtha is required.

Specialized Pipelines: Standard pipelines will corrode or clog. Heated pipelines or high-capacity diluent return lines are necessary to move the “sludge” from the Orinoco Belt to the coast.

Deep-Water Terminals: Specialized loading facilities at ports like Jose are needed to handle the high volumes and specific weights of upgraded crude.

Adding it Up

Above is a high-level list of what will be required to push President Trump’s Venezuelan oil dream into production and profit. Time and money are a factor here, and according to the Administration, American oil companies are going to foot the bill. So, how much is their bill? Here are some estimates:

Immediate stabilization of the current situation and existing infrastructure: $30-35 billion over 2 years.

Grid repair: $20 billion over 5 years.

Upgraders and Drilling: $100-130 billion over 10-15 years.

A rough estimate for the cost is around $200 billion over a 15-year period assuming only minimal setbacks. The highest earning US oil company in 2024 was ExxonMobil with gross profits of $84 billion. It is projected to have lower earnings for 2025 of around $80 billion. For oil companies to make a profit from this investment, they need high oil prices and geopolitical stability, neither of which define our current world. Oil is around $60 per barrel but the break-even price of oil for a project like this is around $45-50. Currently, there’s a chance for some profit assuming no major setback in construction and relative political stability.

The numbers tell the story, and these are just informed estimates. The technology infrastructure alone will likely cost over $200 billion, almost 2.5 times more than the top earning US oil company made in 2024.

If you add up the 2024 gross profits for ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Conoco Phillips, you get $199.69 billion, $310 million shy of what it would take to rebuild Venezuela’s oil extraction and refining infrastructure assuming everything goes to plan and a modest cost overrun.

However you feel about the US’s position in Venezuela today, the fact is that its oil is one of the most significant engineering challenges in resource extraction shy of mining on the Moon. The technological infrastructure required to turn a profit is massive and not cheap.

Maduro probably took his last ride on a navy ship 19 years after I took mine, but over the next decade, a lot of sailors will spend time in the southern Caribbean on warships and oil tankers alike, all burning petroleum to be there.

For more coverage on the energy aspect of the Venezuela situation, check out Energy Common Sense.