Three Chinese Taiknauts are Stranded in Space. Is This Enough for Us to Take the Orbital Debris Problem Seriously?

Orbital Damage to a Return Vehicle Strands Three in Space

When you think about it, space stations are sort of like hotels. At around 250 miles from the surface, the International Space Station (ISS), and its Chinese counterpart the Tiangong, fly around the Earth in low Earth orbit (LEO) and house a select few astronauts from around the world as they conduct experiments in microgravity. A select few have ever had the privilege of looking down upon the Earth from above, and what a sight it must be. Part of the advancement of the space economy is making crewed trips into LEO more common meaning more astronauts from around the world get to look down on the intense blue of Earth. However, in the last couple of years, a few astronauts have gotten a little more than they were bargaining for.

Last week, three Chinese taiknauts were stranded aboard the Tiangong after a piece of orbital debris hit and damaged their return vehicle just hours before they were due to depart. The trio had been onboard Taingong since April 2025 and were due to return last week. The trip home has been suspended and the three taiknauts have an uncertain future looking down upon Earth from above. This is a feeling that was recently shared by American astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore when their mission was extended for 9 months after multiple technical failures with their Boeing craft. Frank Rubio also knows this feeling after this return craft was damaged by a meteoroid stranding him in space for a duration that saw him inadvertently break the record for the longest stay in space in 2023. Coolant leaks resulted in extended stays for cosmonauts Sergey Prokopyev and Dmitri Petelin in 2022.

Taingong Space Station. Image Credit

Taiknauts Wang Jie, Chen Zhongrui, and Chen Dong are the latest additions to this list, and their return date is uncertain as of this writing. But what makes their entries on the list unique is that they are stranded due to an impact of orbital debris. Putting humans into LEO is dangerous enough and experts have long warned of the debris problem creating safety problems for humans and equipment in orbit. As of last week, there is a documented incident where orbital debris stranded three humans in space and was within hours of potentially killing them. Whether this is enough to get the attention of governments and industry leaders will remain to be seen.

Making David Bowie references when talking about space might be bad form, but I can think of no better way to describe the feeling of the taiknauts but to quote Major Tom:

Planet Earth is blue and there’s nothing I can do.

The Debris Problem

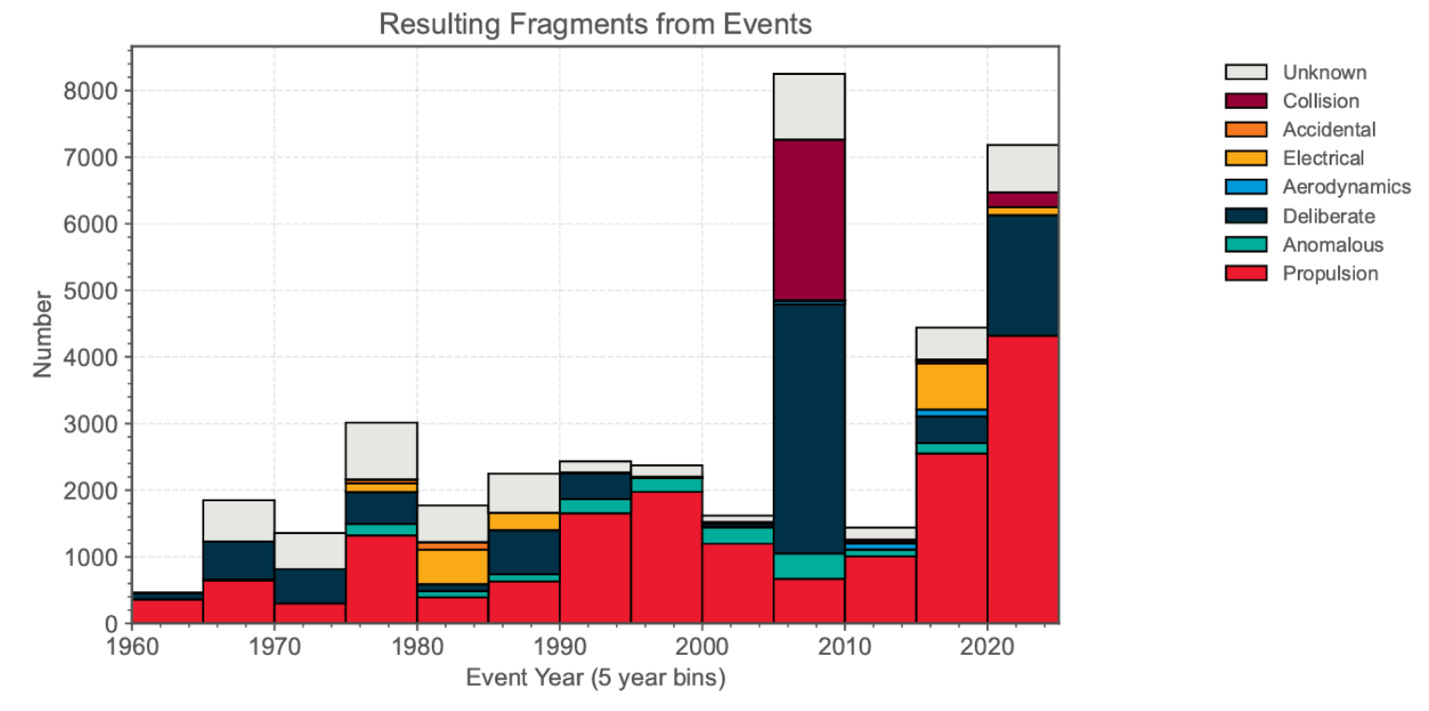

With three taiknauts stranded in LEO due to a debris strike, we should ask just how serious the debris problem is. Should we expect more strikes like this? Many experts have been pushing for a resolution to the debris problem for many years and it has only grown in size and scope in the last five years.

Space is a big place, but we are only talking about a small portion of space. LEO is a band of orbital space that stretches between 160 and 2,000 kilometers above the surface of the Earth. The ISS is usually in the range of 370-460 kilometers above the Earth. LEO is an 1,840-kilometer band that stretches around the entirety of the Earth’s 12,742 kilometer mean diameter given LEO a diameter of 16,742 kilometers. That’s 1.29 trillion cubic kilometers in volume (1.29 X 1012 km3). That’s A LOT of space. However, in the last five years, humans have not only launched a record number of satellites in the last five years but have also created a huge amount of debris in that time. But 1.29 trillion cubic kilometers is an awful lot of space to fill with debris and the chances of getting hit by something in that volume must be small. Until it isn’t and you strand your taiknauts.

According to the United Nations, there were 35,150 tracked objects in orbit as of February 2024, only 25% of which are operational satellites. Today, that number is over 36,000. Estimates are that there are around 1 million untracked objects in LEO for a total mass of around 9,000 metric tons between tracked and untracked. Since 1999, we’ve seen a 50% increase in the number of tracked and untracked objects in space. Those objects are traveling at around 22,000 miles per hour meaning that objects smaller than 1 centimeter carry the kinetic energy of a hand grenade.

With all those tiny and huge pieces of debris on orbit, the volume of LEO starts to fill up quickly. With all those objects traveling 22,000 miles per hour, that volume becomes deadly. According to a 2025 ESA report, the density of active satellites in popular orbital altitudes of around 500 kilometers is reaching the same level as debris making it just as likely that an active satellite will collide with another active satellite as it is to collide with a piece of debris. According to the same report, there are about 10.5 unintentional debris creating events per year resulting from the natural decay of defunct satellites.

So, how bad is the debris problem? Bad. And getting worse.

Already feeling down about our prospects in space? Wait until we talk about Kessler Syndrome.

Kessler Syndrome

It may sound like the next global pandemic, and in a way it could be. Kessler Syndrome is a term for a chain reaction event whereby a significant orbital collision event causes additional collisions creating a mass of debris unlike anything ever seen. Imagine a significant collision at 500 kilometers, a heavily populated area of operational satellites. If one satellite were to collide with another (as the ESA report suggests is likely) the debris from that collision could create a debris field. That field would then go barreling through the 500 km orbital space at 22,000 miles per hour. If any piece of debris at or above 1 centimeter in diameter hits another body, there will be another debris field. This will continue until there are no more satellites to hit. Then what?

If this happened, the entirety of the affected orbital band would be unusable for possibly centuries. Even with a massive clean-up effort, which would require multinational participation, the danger of deploying equipment to that region would be immense. It could also impact future launches to higher LEO altitudes.

Kessler Syndrome has a wonderful sci-fi name, but it is a real threat and the probability of it becoming real is increasing with every debris event, intentional or unintentional, that we encounter.

So, how bad is the debris situation? Yeah. You get it.

How Close is Close Enough?

In the US, space traffic management has been the subject of debate as the US Department of Commerce’s TraCSS system was funded, then wasn’t, then was. Some private companies are attempting to fill the void, but space traffic management is clearly needed to avoid issues like this.

Multiple countries, companies, scholars, and even the UN have called for a concerted effort to prevent further orbital debris creation and clean up what’s already there. The economics of this effort (being that there aren’t any) have so far prevented any real effort to achieve this goal.

But the question that should be on our minds as our Chinese friends settle in for a long haul is whether this incident was close enough. Is this the incident that will spur both policy and technical efforts to mitigate debris or do we need someone to lose their life? Is a minor collision enough or do we need to ruin a whole orbit for a century before we act? The orbital debris issue is not going away and the prospects of debris in cislunar space could be even more dangerous.

The second question is how much debris in that 1.29 trillion cubic kilometers we can tolerate. Space is big and 1.29 trillion cubic kilometers is a huge amount of space. The incident with the Taingong suggests it isn’t big enough. Even though we can predict the trajectories of orbital debris, their speed and the fact that even a tiny piece of debris can cause major problems means LEO is not as large as we think it is.

As Wang Jie, Chen Zhongrui, and Chen Dong look down from Taingong, I’m sure they are over the David Bowie lyrics by now, so perhaps some modified Eagles lyrics will be more like it:

Last thing I remember, I was runnin’ for the door

I had to find the airlock back to where I was before

“Relax,” said the engineer, “We’re programmed to sustain.

You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave this plane.”

After all, Taingong is now a long term hotel that they can’t leave.